This is one of my occasional posts of material left on the cutting room floor of my 2016 book The Monkees, Head and the 60’s. If you like it, check out my book here http://jawbonepress.com/the-monkees-head-and-the-60s/

What’s the connection between Mose Allison, Breaking Bad and The Monkees? We’ll get to the TV show but Allison was (and remains) like The Monkees in being an exception as well as an example in his particular field. He was a white man playing jazz piano, effectively inventing a way of singing which has proved hugely influential in jazz, a kind of adaptation of the sound of a horn put through the human voice. Georgie Fame is the UK’s most famous Allison acolyte, and demonstrates the technique as he takes half the leads on the 1995 album he made with Van Morrison of Allison’s songs, Tell Me Something. A song which isn’t on that album but which is one of his most famous is – in the jazz tradition – an adaptation of someone else’s tune.

‘Parchman Farm’ began life as a blues written and sung by Booker T. Washington (aka Bukka White) as an autobiographical sketch – from 1937 Washington had served time in a state penitentiary in Sunflower County, Mississippi called Parchman Farm for shooting a man in the leg in 1937. His crimes were lesser than those of Huddie Ledbetter but like Leadbelly he was recorded by John Lomax for the Library of Congress in 1939 and he was released the following year. Lomax’s magic touch when it came to securing the early release of his favoured blues singers from jail seems also to have worked in Washington’s favour and he was freed in early 1940. A session in Chicago directly after his emancipation modernised his Delta Blues sound, and caught ths version of the song.

However, it wasn’t until the revival of interest in the early folk-blues recordings amongst the Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan generation that his songs began to be sung and heard by a wider, whiter audience. Dylan famously recorded his ‘Fixin’ To Die Blues’ for his 1962 debut album, a good five years after Mose Allison’s adaptation of his ‘Parchman Farm Blues’ had introduced the tune to the bloodstream of white American music. It emerged on his 1957 album Local Color, a sophomore effort following his dazzling debut of the same year, Back Country Suite. There’s no brass on ‘Parchman Farm’ but Allison is credited with piano, trumpet and vocal for this album and that’s a clue – the easy, highly musical flow of his singing style resembles the cascade of notes from a trumpet and in this regard he’s not unlike Chet Baker who made a similar connection between his horn playing and his vocalising. This new way of singing came from and still belongs to jazz – it may well better suit scat, from which it is partly derived, but when there’s a great lyric it lends a song a fluvial impetus which is hard to resist.

Bukka White’s 1940 recording is a tight little country blues which showcases his rough-edged baritone bleat. It’s powerful and a real palate-cleanser. It’s also quite unlike the Allison adaptation, even more so than the difference between that version and the Monkees’ work on the theme. So ‘Goin’ Down’ is just the next stage of music being handed from player to player, from age to age. White himself has been sampled by a number of hip hop and electronica acts. The circle remains unbroken. Whoever it was who suggested that the song was sufficiently unalike its apparent source for it to exist in its own right was correct – for example, Allison’s skipping piano triplet leads his 1957 vocal take, and there is actually no keyboard at all on ‘Goin Down’ (although, prior to writing this, I’d have sworn there was a mighty Hammond organ pumping away in the mix there somewhere – strange but true). Typically for jazz the voice sits in the arrangement as another texture, another element, the formal verse structures a lyric delivers simply a structure on which to drape the music.

When the song breaks down into a half-speed blues piano lament towards the close we think it’s going to end that way, but it provides a platform for the final bleak gag of the song ironically sung brightly over a final restatement of the nimble little piano riff: that last line is ‘I’ll be sitting here the rest of my life/ And all I did was shoot my wife’. For some reason that final twist reminds me of the last scene of Head – it’s a similar technique- take them to the edge of a resolution and then show them that the truth is something different. In truth when heard side by side, all the songs truly share is a spirit of openness and the use of an, insistent, busy little riff that serves all around it.

Just in case we are unclear about this song’s potency, here’s a clip from a BBC documentary which focusses in on the significance of ‘Parchman Farm’ for the musical peer group of The Monkees, including Georgie Fame and Pete Townsend.

Peter Tork will likely have learned the song from Allison’s Local Color and when the liberty of the studio sessions which produced Headquarters and Pisces Aquarius arrived they could explore any musical avenue that suited them, trying them out and trying them on for size. You only have to listen to the musical variety of the latter for proof of that. Chip Douglas told me that he recalled the idea to start playing around with ‘Parchman Farm’ came from Peter at a session in June ’67, no doubt because it’s a tough sounding, infectious little riff to play with, that sits up and begs for reinterpretation, to be remade as something new. Here’s an occasion where the newborn nature of The Monkees as a music making unit definitely worked in their favour – they took an idea and ran with it – and the groove that is ‘Goin’ Down’ developed from a jam at the ‘She Hangs Out’ session. At first just a funky little instrumental thing, with Tork and Nesmith on electric guitars, and the rhythm section of buddies Eddie Hoh on drums and Chip Douglas on bass. As is often the way when a little musical phrase is borrowed it is also developed – and this is why jamming between musicians around a riff you like is always better than sampling – and by the end they had decided that it didn’t really sound so much like ‘Parchman Farm’ any more, so why not make it one of their own?

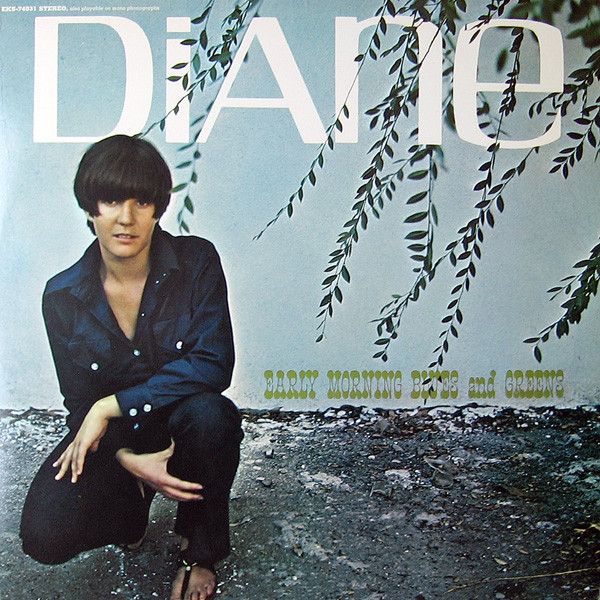

Diane Hilderbrand, who had already contributed to their catalogue notably by the stunning small-hours impressionism of ‘Early Morning Blues and Greens’ on Headquarters was sent the tapes and invited to come up with a lyric. So the tune has a five-person credit, tying it for ‘longest list’ with ‘No Time’, with which it shares some headlong energy yet in both cases the tunes never quite tip into simple speed – there’s control there, via the arrangement and the playing, and that’s what makes the variations in pace so satisfying.

The speed and ease of Hildebrand’s contribution only emphasises that ‘Goin’ Down’ was a genuinely spontaneous creation in the studio, the kind of thing that can only happen when people are getting into playing with each other as a unit. In a wider ranging interview for my book The Monkees Head and the 60’s Chip Douglas described Lester Sill to me as ‘initially there to make sure things didn’t get too far out but ended up contributing plenty to the songs. Bless him, he was always right!’, and it was indeed Sill who suggested they work on the jam and draw a Monkees original out of it, securing Dolenz for the vocal and suggesting horns – unlike the TV show version of ‘She Hangs Out’ there are horns on the Pisces version arranged by Shorty Rogers and it was he who sorted the brass for ‘Goin’ Down’, which was added to the basic track nearly three months later in mid September ’67.

There are a dozen players on there, some but not all also to be heard in more restrained mood on ‘Hard To Believe’, which received its dose of horns at the same session on the 15th of the month. LA jazz notables all, they were no doubt glad of the pop money the session provided but they blast the roof offa the sucker, notably the unidentified trumpet player who soars high over the closing sections, really giving Dolenz a satellite to bounce his vocal off. It’s an amazing sound, and the last thing one would expect to find on the b-side of ‘Daydream Believer’ – it must have been a turn off for many, but a musical education for plenty more.

‘Goin’ Down’, as you can hear above on the original 45, is in every sense a blast. Musically, rhythmically, lyrically. You can hear the freedom in the way it just goes and goes – more than once you think it must be through as the horns and drums reach a great tumult but then they settle back and the funky little guitar lick surfaces once more, propelling the tune along, and back comes Micky. Unlike ‘Parchman Farm’ this song is packed with words. Diane Hilderbrand’s lyric is a corker – in its literal sense it starts off as the story of a failed suicide but I see it more as an exploration of the possibilities of matching language to rhythm – the flow of the lyric as sung by Dolenz is concomitant with the flow of the music and both are perfectly matched to the theme of being carried downstream. Not in the ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ sense though because the character in this song is wide awake and, possibly for the first time in years, his mind is switched to full on. The starting point for the idea of ‘goin’ down’ is the jump into the river by the rejected lover, and what she will feel when she finds out what has happened:

‘And I bet she will regret it

When they find me in the morning

Wet and drowned

And the word gets ’round…

Goin’ down’

Yet the first word of the verse is ‘floatin’, as aopposed to ‘drownin’ or even ‘sinkin’ – the buoyancy of the man and his saturated liver is reflected in the flow and forward motion of the music and the endless strem of words, keeping him from sinking into the silence of the waters. The song is upholstered with dark humour – when he does go under, he’s back pretty quick :

Comin’ up for air

It’s pretty stuffy under there

I’d like to say I didn’t care

But I forgot to leave a note

The narrator’s mood goes from desperate to struggling to survive to relaxed and finally resolved to dive back into life and live it more fully. So in that sense it’s almost like a little morality tale. But among the drama of its musical dynamics and the hitherto undisclosed evidence of Micky’s jazz singing skills you’d be forgiven for not noticing this at first.

We could read the river almost as the river of time, and the flow of the song a sketch of how you slowly recover from a moment of crisis. The subject sobers up as the song goes on in more ways than one. ‘Now the sky is getting light and everything is gonna be alright’ and there is a supernatant quality to the track. It’s all mouth music, all that blowing all those words, struggling for breath fighting for breath to keep breathing, struggling against its own form to keep going to keep afloat. When I listened to it as a kid it made me think of suffocating – as a mild claustrophobic it’s still an uncomfortable listen at times for that very reason.

The song is ushered in – not inappropriately – by a swiftly descending run on the bass, played by Chip Douglas, accompanied by full-fat jazz skitter on the kit by Eddie Hoh, over which Micky intro’s his vocal with a slightly self-conscious ‘Sock it to me!’ – poised midway between the simple act of singing in a certain style and more complex awareness of what it means to be singing in that same certain style. The phrase was certainly current in the 60’s, meaning ‘let me have it’ or ‘give me your best’ in personal or business contexts but also had a sexual connotation, an invitation to, well, give someone your best effort. It was also part of pop culture, travelling from jazz-speak into the mainstream via the hip talk that stetches right back to Slim Galliard, picked up for White Americans through the growing popularity of jazz in the 50’s and early 60’s and also the writings of the Beats in general and Jack Kerouac in particular.

Around the time Dolenz was recording this track Aretha Franklin’s mighty version of Otis Redding’s ‘Respect’ was a big hit and included the phrase ‘sock it to me’ as a kind of chant – showing how far it travelled it later became a worn-’til-it-was-thin catchphrase on the big TV show of the late 60’s, Rowan and Martin’s Laugh-In , which was fleetingly proposed by Davy Jones as a possible model for any third series of The Monkees. Indeed almost one of the last professional obligations the Tork-less trio fulfilled was an incongruous appearance on this show on the 6th of October 1969.

Micky’s mix of musical and actorly skills serve him well in ‘Goin’ Down’ as he takes on Hildebrand’s snaking, seemingly self-generating stream of words and turns them into one of his finest vocal performances. he gets stuck right in, using a style which is effectively scat-singing with all the rhythmically responsive twists and turns that involves, only with actual lyrics to get his mouth around. That’s the most remarkable thing ; the song contains over 600 words delivered at a speed both excitingly rapid – something is happening here, so keep up! – but also measured enough to be heard and understood as they flash by. The studio version may well be a composite of a number of takes but live he does this song straight and, as a former singer in a former band myself, I can tell you that it’s no mean feat.

The lyric maps out moments when one’s life flashes before one’s eyes : the jump (‘Floatin’ in the river with a saturated liver’), the struggle to survive overcoming the emotional upset, with instinct overpowering reason (‘Comin’ up for air, it’s pretty stuffy under there’) the moment of reflection after the crisis has passed (‘I should have taken time to think’) which gives way to realisation (‘And now I see the life I led, I slept it all away in bed, I should’ve learned to swim instead’) and finally resolve to make things different (‘If I could find my way to shore I’d never, never do this any more’) and even plans an escape route (‘I’m floatin’ on down to New Orleans, and pick up on some swingin’ scenes’). That mention of New Orleans is of course the musical clincher – he’s headed for the spiritual home of jazz music – that’s where this rhythmic river has led him.

The breaks between each verse help build a dramatic sense of, well, goin’ down. The verse are busy and chug along very smartly driven by guitar bass and drum but also benefit from punches of brass on each beat which both soften and toughen the rhythmic steps of the tune. On the last two lines of the first four verses ( that is, ‘drowned/round’, ‘shoes/news’, ‘shore/more’ and ‘town/brown’) the instruments drop back leaving Dolenz’s voice – surfacing to catch its breath, perhaps – accompanied by staccato punches from the ensemble before all tumble back into the rolling waters once again. As the song’s momentum builds, rising and falling toward the climax these distinctions disappear as the song’s narrator starts to feel comfortable in this environment (‘just floatin’ and lazin’ on my back’); this new sense of freedom is expressed through a more unified rhythmic structure.

The sax solos at 0.40 and 1.25 allow some breathing space and over them Dolenz intuitively scats in a more orthodox manner ‘ Hep hep, hep hep !’, the kind of rhythmic jazz-speak you’ll hear in any performance of old-time jazz. He had the vocab to hand. He’d already proved his chops at r’n’b and soul shout singing in the little James Brown skits on and around ‘Mary Mary’ in the live shows as well as some great studio performances up to this point and this humour leaven’d approach to his craft can sometimes obscure how good he was at this. The instrumental mid-section (1.25-1.40) flows straight into the lengthy fifth verse (‘I wish I looked before I leaped…’), and I love how the band pulls back for the lines where he changes his mind about what’s best for him

The song has a curious place in the band’s catalogue – it was an incongruous marketplace partner to ‘Daydream Believer’, for one. (Daydream Believer’ would get another odd bedfellow on The Birds The Bees and The Monkees of course, being pursued by the wig-flipping ‘Writing Wrongs’)

It also pops up in odd places in the TV shows, being heard in five episodes, twice as ‘romp’ music, then as one of four in the song-heavy ‘Monkees In Paris’ episode verite, and once, in the opening moments of ‘The Monkees Paw’, we get a brief glimpse of them ‘finishing off’ a ‘live’ version (which is simply playback) as an audition for a club owner – Micky raking the tambourine high , Peter thrumming the bass as well he might. Here’s the whole ‘Monkees in Paris’ episode, a particular favourite of mine, for its views of Paris a la 67 as much as our favourite chaps. ‘Goin Down’ comes and goes in the musical montage.

It’s impossible to write about this song without mentioning the clip of Dolenz performing the song which appeared in two episodes. As soon as you start researching the band’s story you realise how complex it is, and how quickly things happened, which can be confusing for the cultural scholar or historian trying to make sense of it all. This clip is a good example, featuring a live vocal from Dolenz over the backing track frontloaded onto the tenth episode of the second series (and number 42 in all) ‘The Wild Monkees’ and Finally, the performance clip we can find on Youtube is the track as heard on vinyl simply matched to Dolenz’s performance as seen in ‘The Wild Monkees’. Still with me? Good.

That performance clip is interesting to us in several ways – it features Dolenz only, soft-shoeing around on a darkened stage in cream trousers and a dark, high-round-necked silk shirt we might more readily expect to see Jones or Tork wearing. There is however much to see – the camera goes to town, using reproduction to split Micky into five, and gives us an early look at the solarisation that would be more fully and spectacularly realised in the opening and closing sequences of Head the following year. An almost hidden feature of the clip – certainly hard to see on our small British TV in the early 70’s, is a sax and a bass guitar, apparently ‘playing themselves’ but on closer inspection (unavailable to viewers pre- video recorder of course) they are being held and played by black clad, black-gloved musicians, a standard technique in the theatre of course but new for pop which is supposed to be all about the visibility of the musicians, as the four Monkees knew all too well. This visual playfulness also has a high-art gloss to it, and the ‘black on black’ method was a key part of European theatre of the age of Aquarius. There’s no effort to reveal the musicianship, yet the vocal is live live live. It’s a beguiling mixture.

‘Goin Down’ is a song which has been a beneficiary of the reappraisal of the Monkees song catalogue, providing a showcase for Micky Dolenz in concert for many years now, allowing him to demonstrate how much of that Satchmo gravy he has in his voice for real now and as such proved a highlight of 2019’s live album.

The song’s cult reputation led to it cropping up unexpectedly (especially to Micky) in the hit TV series Breaking Bad; the show made a habit of matching music incongruously to scenes and so it was with ‘Goin’ Down’ accompanying scenes of meth ‘cooking’. It featured in ‘Say My Name’, the seventh episode of the fifth and final series, broadcast in August 2012. Micky confessed to being a ‘little torn’ about the musical use, but was clear on what he gained from it : ‘I didn’t make a penny’.

Finally an observation about Micky’s performance on this track – he could very easily been out of his depth with material like this and his success in the task is at this distance perhaps easy to underestimate – but think, could Jones, Nesmith or Tork have done this? Not for me, no. For that matter could Jagger, McCartney? Hmmm…unlikely. Stevie Winwood, Van Morrison? Maybe. But Micky did do it and even taking into account his own modest self-appraisals, we shouldn’t gloss over a performance of this calibre.

Now the sky is gettin’ light, and everything will be all right…

Awesome stuff- as always. 👏

LikeLike

My fave was “my pappy taught me how to float, but I can’t swim a single note” thru me in to teach me how, and I wound up floatin’ like a mama cow!

LikeLike

One of many amazing Monkees songs most folks never heard

LikeLike