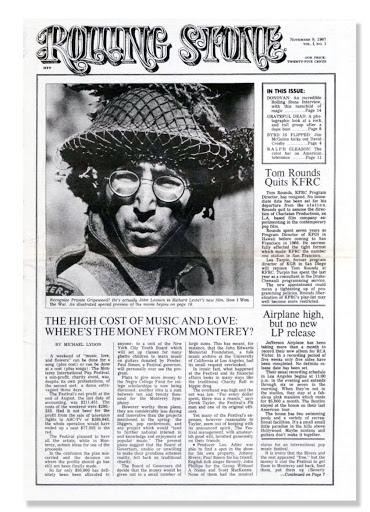

Does anyone remember a show on Radio 1 (in the 247 Medium Wave era) called ‘My Top Twelve’? It was kind of like Desert Island Discs but for pop musicians. Saturday mornings, hosted by (I think) Paul Gambaccini. It was the first place I ever heard Van Morrison (courtesy of Leo Sayer, believe it or not) and where I learned that Art Garfunkel and Paul Simon had fallen out. From Art Garfunkel. This was all news to a very young me. Anyway this blog is going to be a bit like that show – except it’s me, not Leo or Artie, choosing and chuntering about records and recordings, songs and singers, music and musicians of many flavours. As Brian Wilson said, well, well, you’re welcome…

Christmas Monkee Business

In the spirit of Samuel Beckett’s ‘Mirlitonnades’ – literal and literate scraps he wrote on torn envelopes and ciggie packets (he smoked Gauloises) – I wrote the following piece in around 33 and a Third minutes for an ‘instant book’ an acquaintance was assembling on the subject of Christmas Music. It’s probably for sale somewhere but I’ll post my contribution here as it will cease to be topical in a fortnight. So here you go.

The Monkees only existed as a recording entity for three or four Christmases, 1966-70 at a push, but it’s still surprising they didn’t put out a Christmas song of any kind over that period given the scale of their success and the breadth of their appeal. Yet they do now have a compact and bijou Christmas catalogue, including at least one bona fide gem.

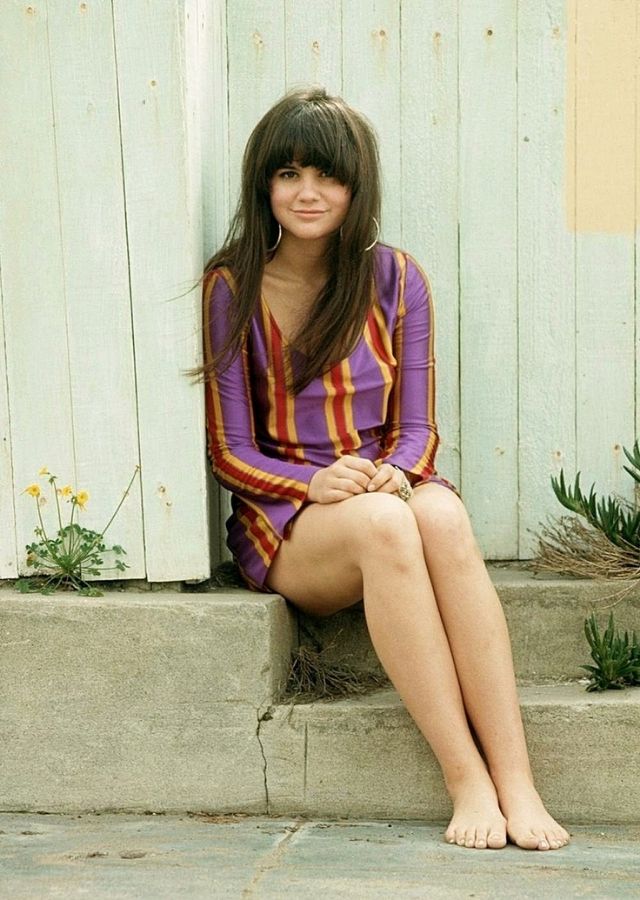

Their first foray was recorded, improbably, in the blazing summer of 1976. A standalone 45, ‘Christmas Is My Time Of Year’ was a tune written by their mentor and producer Chip Douglas and his fellow ex-Turtle Howard Kaylan. The song, bright and direct but also sophisticated in form in that Turtle-ish way, had first been recorded in 1968 on a Douglas-produced single credited to ‘The Christmas Spirit’, a sort of LA supergroup-in-waiting featuring Linda Ronstadt with Gram Parsons, among other luminaries of the scene and era.

In 1976 Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones linked up with key Monkee songwriters Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart in a kind-of Monkee reunion project called, well, Dolenz, Jones, Boyce and Hart. They recorded one album of original material for Capitol in ‘76, and undertook hugely successful tours of the US and Japan, often playing at theme parks, tapping in to the first stirrings of 60’s nostalgia among their original audience, now adults, parents and mortgage payers. This itinerary included a show at Anaheim Disneyland on the Bicentennial July the 4th which featured a cameo from a very long haired and bearded Peter Tork.

Lines of communication patched up, later that same year Dolenz, Jones and Tork recorded ‘Christmas Is My Time Of Year’ as ‘We Three Monkees’ – the unique torment of being a Monkee meant that the ownership of and therefore freedom to use the band name/brand name ‘The Monkees’ was out of the hands of the actual group members . It was produced by Chip Douglas and pressed and distributed privately on his own ‘Christmas Records’ principally for sale at the developing market of Monkee Fan Conventions. The record attracted more attention than the protagonists thought it would, and a promotional video clip was produced which featured a surprise revelation of the identity of Father Christmas at its close (spoiler alert: he was tall, Texan and sometimes used to wear a wool hat). nb it’s not on Youtube currently so here is the audio instead.

Before their symbiotic relationship with Rhino Records blossomed in the 1980s Monkee activity tended toward the random and mercurial, so this interest was to fall back until the advent of MTV – arguably the world’s way of catching up with The Monkees and effectively invented by Michael Nesmith (see my book The Monkees, Head and the 60s for the full story). MTV showed 45 episodes of the TV show back to back on their ‘Pleasant Valley Sunday’ on the 22nd of February 1986, turbocharging the group’s upcoming 20th Anniversary celebrations and rekindling Monkeemania. A reunion album, Pool It!, emerged in 1987 – sans Nesmith, who was busy with his pioneering film and video entity Pacific Arts.

Further Monkee reunions would take place frequently on stage and twice on album – Justus (1997) and Good Times! (2016). By the time the next Christmas record appeared Davy Jones had passed on and the Monkees’ critical stock had risen to lofty levels, consolidated by the rapturously received Good Times!. Christmas Party (2018) is good to have, but, like any Christmas album, it can’t be many Monkeemanics’ favourite long player. Produced, as was Good Times! , by Adam Schlesinger of the band Fountains Of Wayne, it is a patchwork of familiar standards (‘The Christmas Song’ which you never expected to hear sung by Michael Nesmith), folk-hymns (‘Angels We Have Heard on High’ a characteristic collision of tradition and innovation from Peter Tork) and selections from the pop songbook, some obvious (Paul McCartney’s ‘Wonderful Christmas Time’), some more obscure (Big Star’s ‘Jesus Christ’). It also includes a few bespoke commissions, notably by Andy Partridge of XTC (‘Unwrap You At Christmas’) and Rivers Cuomo of Weezer (‘What Would Santa Do’), both brilliantly brought alive by Micky Dolenz. Davy Jones joined the party via pre-2012 recordings, including a typically warm and welcoming version of ‘Silver Bells’. Only a Monkees record could accommodate such a range under a single banner. Therein lay their strength and problem.

In a very modern marketing twist, the version only available in branches of US record store chain Target Records appended the Baker’s Dozen cuts with ‘Christmas Is My Time Of Year’ and ‘Riu Chiu’.

‘Riu Chiu’? Follow me.

While it feels surprising that while The Monkees didn’t issue a Christmas song in their original iteration what they did do was make a Christmas episode of their TV show on the theme, sensibly entitled ‘The Christmas Show’. For a band born to be on television I suppose it makes a kind of sense that TV prevailed. Aired on Christmas Day 1967 in the US and early 1968 in the UK, it sees the foursome show the magic of Christmas to a neglected child. The show featured no Monkee music or ‘romps’ (the chase and skylarking sequences soundtracked by and showcasing fresh Monkee tunes featured in each episode) instead giving us en passant earfuls of seasonal standards. It also features a famous closing title sequence where Davy introduced every member of the TV show’s crew. A sample of this is used on the title track of Christmas Party, a co-write by Monkee fans Peter Buck of REM and Scott McGaughey of The Minus Five.

The one original tune in the programme provides the final moment of the episode, preceding the good naturedly anarchic Cast and Crew introductions. Uniquely among Monkee performances, it’s an a capella performance, all four members of the group singing together in close harmony. The song they sing together is ’Riu Chiu’, a 15th Century Spanish Christmas song, in the villancico form – a kind of sacred folk song. It arrived in the USA from the South, moving up with migrants from Latin America. The title literally means ‘Roaring River’, although it is also associated with the sound of the song of a nightingale. Either way, its subject is the Nativity of Christ. The Monkees will have learned it from producer Chip Douglas – such a key figure in Monkee history – who had recorded it in an identical arrangement with his band the Modern Folk Quartet on a 1964 album, Changes , which coincidentally was the original title for The Monkees’ 1968 movie Head and became the title of the last gasp Monkee album from 1970 which featured only Dolenz and Jones. So the circle goes unbroken.

Sitting together in front of a Christmas tree festooned in multicoloured lights it looks seasonal enough, but once they begin singing you’ll get a surprise. Here we get complex four piece harmonies, sung a capella in a blend of medieval Catalan and Spanish. Micky Dolenz takes the verses, and sings them with perfect ease, while Peter, Michael and Davy join in the four part harmony on the choruses. All four are en pointe: Michael is lost in the creative moment, while Peter looks the happiest I ever saw him, and there’s a treasurable moment when he and Davy exchange quietly delighted glances as Micky sings the second verse. Appropriately the closest thing to it from the Christmas Party sessions is Peter Tork’s lovely ‘Angels We Have Heard on High’. They attempted a studio recording, issued years later by Rhino, but the version on ‘The Christmas Show’ is furlongs ahead of it. It also somehow captures the quiet beauty and mystery of Christmas, the silent partner to the brazen commercialism. ‘Riu Chiu’ is a rare occurrence of all four Monkees working together in the here and now toward a common goal, untrammeled by the business concerns that forever swirled around them. Be my guest and check it out. And Merry Christmas!

A Dream Where The Contents Are Visible: Van Morrison’s ‘Poetic Champions Compose’ (1987)

If you have seen the current expensive looking advert for Cunard’s expensive looking cruises (‘I wonder, I wonder…’) you have heard the voice of British philosopher Alan Watts (1915-1973). This reminded me of a favourite Van Morrison song, ‘Alan Watts Blues’ from 1987, tucked away in the middle of side two of perhaps the smoothest of his albums, Poetic Champions Compose. Watts and Morrison were both living in Marin County, California in the early 70’s and I’d like to think they crossed paths. So when I heard the album at a friend’s house last week I was reminded that I had written about the record for my book on Morrison Hymns To The Silence (Bloomsbury 2010). Buy the book here, folks:

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/hymns-to-the-silence-9780826429766/

Most of the section on PCC fell onto the cutting room floor – the original manuscript was over twice the length of the published version – so I thought I’d post it here. It was part of a section on how Morrison worked in the studio so is particularly attentive to that aspect of the record. It’s a great album, so please take this as a recommendation to check it out.

Recorded over summer 1987 at the Wool Hall Studio Beckington and London’s Townhouse, Poetic Champions Compose offers an interesting case study in how Morrison constructs and fashions an album in the studio, pulling together aspects cherished from live performances and placing them into the very different environment of the large, comfortable multitrack studio. The risks taken in live performance can be attempted in the studio, for sure, but there is the safety net of the retake or the overdub to make good any fluffs or over-reaching. How much use of this advantage does Morrison make?

Wool Hall was a studio in Beckington in Somerset, originally owned by Bath-based British pop duo Tears For Fears, and built with the substantial earnings from their hit singles and albums in the period 1982-86, when they were among the biggest sellers with both pop and rock audiences, their appeal spreading from Smash Hits readers to the rock critics of the then-new glossy rock monthly magazines. The studio was appropriately well-upholstered and , as they say, state of the art in its provision. For Morrison it also had the advantage of being close to his then-home also near Bath, and being ‘down by Avalon’. Another Bath boy, Peter Gabriel, had set up a studio in the area in Box village and Box Studios became synonymous with Gabriel’s RealWorld Records; it was local, but Morrison’s only musically productive visit to was to record a version of Bobby Womack’s ‘That’s Where It’s At’ with The Neville Brothers for a RealWorld compilation.

The studio was initially as one might expect set up purely for the use of its owners and designers but in the wake of the global success of Songs From The Big Chair (and their struggles with the very expensive and commercially damp follow-up The Seeds Of Love) Tears For Fears opened the studio for commercial use. Van Morrison was one of their first customers, using the studio for to arrange, plan and record Poetic Champions Compose over a few weeks in the summer of 1987. He was preceded in the studio, as it happened, by The Smiths who recorded their last album Strangeways Here We Come at the studio in Spring 1987, and the etching on their single from that album ‘Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before’ was ‘Murder at the Wool Hall (x) Starring Sheridan Whiteside’. So it was certainly the studio de jour.

Initially, Morrison intended the album to be the instrumental disc he had been planning for some time and the environment helped him relax into such non-mainstream ideas – remember that it was both at and behalf of Moles Club in Bath that Morrison participated in the recording of Cuchulainn in 1982. Indeed the album features three substantial instrumentals very much developing the mood and model set down by ‘Scandinavia’ and ‘Evening Meditation’, among others, in the preceding five years. As he noted to Martin Lynch the following April in Coleraine, when asked about using ‘different forms’ :

Lynch: Are you looking to develop different forms for your work…like instrumentals?

Morrison: Oh, yeah, I’m still developing instrumentals…I cut three on my most recent album’ [meaning PCC]

The album begins and closes with sax and piano instrumental pieces (as did the second vinyl side), very clearly shaped from the same raw material in the room at Wool Hall, but in the end though these pieces placed at key positions in the sequence guide the tone of the album, they don’t dominate it. This is in no small part down to the quality of the songs and the vocal performances that occupy the other eight berths on the record. In Clinton Heylin’s book, trumpet player Martin Drover remembered that

…it was a jam, that album…we went to the Wool House [Hall] and we sat there, looked at one another.’What do you fancy, Van?’ Sod it, let’s just have a play. You don’t usually do that – you’ve usually got some dots in front of you. The first couple of days Van was just playing alto, we were just busking, playing over things…stuff evolved out of that, and that’s how that album was made…he was fairly relaxed.

The professional session musician’s fear of the empty page seeps through here (“we sat there and looked at one another…you don’t usually do that- you’ve usually got some dots in front of you”) , but clearly Drover soon relaxed into the process. Enjoy these ‘Spanish Steps’, the album’s opener.

Drummer on the sessions Roy Jones recalled that once the songs had evolved in the way the Drover describes “it was mostly only one take, perhaps two takes, no more, then repairs”. This methodology is familiar in its adhering to the ‘one take’ philosophy Morrison used and also aspired to – think of the eulogy to Sinatra’s technique in ‘Hard Nose The Highway’, described by Morrison: “The first verse is an image of Frank Sinatra going into the studio and saying ‘Let’s do it’. he makes an album then takes a vacation. It’s an image of professionalism”. It is interesting that this idea has such a strong appeal to Morrison in terms of how he views the art and/or labour of making records , by their very nature definitive to an extent that a live show is not. As he told Uncut magazine in 2005, “I didn’t get into this to put records out” , and so we can see the appeal for him of treating the recording studio as an extension of the live stage, recording as a kind of snapshot of a starting point for a song rather than being the end of the road for its growth. Yet the most casual listen will tell us that the songs on Poetic Champions Compose are not rough and ready, but sophisticated and carefully constructed pieces of work, functioning at a highly refined level. The trick, if we may call it that, is for the song to be both subject to such processing while retaining the kick of the new. It takes an expert touch both in composition and arrangement.

Fiachra Trench told me how the arrangement which graces one of the albums key songs, ‘Queen Of the Slipstream’ came together:

‘Queen of the Slipstream’ is one of the tracks on Poetic Champions Compose, the first album on which I collaborated with Van. It was a first for Van also: his previous string sessions in the USA had been for a smaller section than I used; I think we had about 26 players. The string session went very smoothly. Van very content. On ‘Queen…’ I reduced the strings to a chamber group for Van’s harmonica solo and the second bridge which follows. Otherwise it’s the full section. (These days Van favours smaller string sections — from string quartet up to, say, 10 or 12. More organic. Less orchestral.) There’s an epic feel to this track and the strings seem to enhance that feel.

Some of the string lines are derived from Neil Drinkwater’s piano lines. I often use that technique when writing string arrangements; it helps to make the strings sound more part of the track, less like an overdub, less pop.

The sheer beauty of ‘Queen Of the Slipstream’, in my view his greatest lovesong, is musically analogous to the album of which it is an integral part, and a form of meditation in itself: rather like Veedon Fleece it was somewhat lost, and where the former was directly after the 1973 live album, Poetic Champions Compose was overtaken very quickly by The Chieftains project. Indeed the only performances of these songs by the band who recorded them was at the ‘Secret Heart Of Music ‘ conference held at Loughborough University over the weekend of 18-20 September 1987, where Morrison played sets on both evenings and also contributed to panels and discussions over the weekend. The album is little sound world, sounding very studio based, even though it does of course have a ‘live ‘ feel to it. It’s this conundrum that must interest us. Tracks like ‘Celtic Excavation’ evoke the ‘mystery’ of the Celtic without making any musical reference at all to ‘celtic music’ as widely understood. The album’s mode is conducive to, if not dominated by the instrumental, and this is something less easy to do onstage.

‘Queen Of The Slipstream’ is the album’s key song, the lyric of which contains the album title, as well as references to ‘Astral Weeks’ in its title via a distinctive Morrison term – the slipstream – and ‘Come Running’ : ‘ I see you slipping and sliding in the snow…you come running to me, you’ll come running to me’. This song represents perhaps his best example of the blend between the ‘mystic’ song and the love song for which he would subsequently be well-rewarded (‘Someone Like You’ on the same album, ‘Have I Told You Lately’ later), in its fusion of the mystic and the material, the spiritual and the corporeal. The ‘innocence/experience ‘ motif which frames the lyric exemplifies this. It also employs some of his key motifs beyond this sensual bi-polarity, with the two apparently contradictory or antagonistic states being yoked together and experienced simultaneously . How does the sound of the song help achieve this tricky balance and help the feeling of perceived wholeness to be realised so sweetly and effectively?

A synth harp opens picking an escalating scale of 7 steps up to entry to the ‘scene’ of the song; we need to climb to reach this place, to start the journey. It is as if a casket or treasure box is being opened slowly to us, the brightness within revealed. This is the ‘Queen’ motif which continues under the verses, rising and falling in proximity and consciousness, slipping in and out of conscious hearing but always present as an underpinning and essential element of both the composition and the sense of connection, identity, a kind of ‘leitmotif’ within the life spirit of the song. It is certainly used this way in the Moondance movie, where ‘Queen Of the Slipstream’ is Anya’s theme, cleaving as closely to her as ‘Moon River’ does to Holly Golightly in Breakfast At Tiffany’s. It keeps the rhythm on track and is appropriate to the impact, both revelatory and stabilising, of the object of the song, both precipitated by this idea and also the subject of it. Morrison’s guitar picking starts to drift in , introducing a grittier level of perception and element within the music itself. The strings arrive at 13 seconds, moving like a slow comet across the rhythm track, traced by Morrison’s unity hums twice (at 13 and 20 seconds: two more divisions of seven).

The vocal enters, seven seconds later, at 27 seconds and the strings reach a periodic crisis to usher in the lyric, and the Queen leitmotif surfaces again alongside. At the one minute mark, at the lyric ‘there’s a dream where the contents are visible’, the string line illustrates this revelation, as it follows the synth line for the next time round at 1:08, an octave down. Four pulses of the strings arrive, drawing sensuously , not clipped or stark, up to modulation at ‘Going away’. June Boyce ‘s vocals join Morrison here, and at 1:49 the tambourine enters, bringing a new slightly accelerated pulse as a feature of the larger movement; a kind of internal swiftness at one with the steadier movement, adding to this harmony achieved beyond the apparently contradictory or agitant constituent elements. We get a sense of both earthly movement, in solid (Spanish) steps and also sense of floating, lightness, an escape from ‘This Weight’ the thing that keeps us tied to the earth or our movements prescribed: on ‘Motherless Child’ he wishes he could “fly like a bird up in the sky…a little closer to home” . This image serves to convey the sense of both exile from a place of refreshment and harmony but also an awareness of the physical pleasures and limitations of the body; so images from Buddhist karmic reincarnation, Christian scripture and pre-Christian Greek mythologies (Icarus, for example) are melded via a blues progression in a line or two. Lightness and heaviness, corporeality and spirit come together. An alchemic motif, seen already on The Mystery ‘(all your dirt will turn into gold’), is introduced here: “Gold and Silver they place at your feet my dear…but I know you chose me instead”. Love is greater than material wealth and spiritual well being better than material comforts.

Fiachra Trench told me of the song’s mid section that “I reduced the strings to a chamber group for Van’s harmonica solo and the second bridge which follows”. With the strings thus reduced to a quartet behind this section, the harmonica adds some r’n’b grit to the sweetness, and here again the two disparate elements combine to create a brand new texture; the harmonica and string quartet together give this sense of wholeness of body/soul, weight/ lightness, corporeal/spiritual, spiritual wealth/material wealth. All of these are co-present and almost because of their differences achieve a new harmoniousness and spiritual agreement.

The strings at 2:50 become much denser, building to an emotional climax. The sense of lightness and freedom for the last ‘Queen’ riff re-emerges and consolidates whilst pushing the song, and the idea on unto it’s proper resolution, represented by the strings vaulting up like the rhythms of a poem or a head upturned to the open sky, return to in the last section to the lyrical innocence/experience theme. From 3:35 on the song builds to the sustained climax: it is still building in a way as it fades finally at 4:50, suggesting that it extends way beyond its own modest temporal span. Lyrically it return to the initial imagery, in a movement cyclical yet linear and progressive: we are in a different place from where we were at the beginning . This is demonstrable evidence of a kind of wholeness both sequential and evolving, ever-present and unchanging: we return to the source , changed by the journey, moving freely between innocence and experience. This apparent paradox is in some ways a possible interpretation of the ‘meaning’ of the term ‘slipstream’ in Morrison’s work.

Morrison’s voicing of the word ‘snow’ at 3.55 and his extrapolated ‘Queen’ at 4.12-4.14 provide the vocal peak of the song, and this goes close in hand with the musical climax, with the strings at their most abundant and free between 4:15-23. These details link with the beginning too in that Morrison’s voice shadows the guitar line in his union singing style down to the fade, two distinct elements moving in agreement, creating an entirely fresh and ‘ other’ element which still maintains and establishes an new wholeness within itself. This mix of smooth surfaces and complex emotional memory – exemplified perhaps by the blend of harmonica and strings – is indicative of the album’s whole sonic mood . The album has a very definite sound but not necessarily that which we have identified as through composition, being more to do with who was in the room at the time, the mood and the environment – recall that Martin Drover remembered the album initially being ‘busked’ up from the ground; Morrison clearly liked the ambience of the studio and the way his music felt when recorded there. Wool Hall suddenly seemed to fit the bill in regard of what he was looking for at the time, and in 1994 he bought the studio, reverting to more or less private use. Ben Sidran recalled to me how the recording the Mose Allison covers album Tell Me Something took place there, and the impact of the atmosphere of such a familiar environment:

“It took two afternoons. It was just a groove. I had prepared charts of all the songs based on the charts we had used in the original Mose sessions. We just passed them around and ran the songs down. The spirit was very loose and relaxed. All music…. We were set up “live” in the studio – that is without baffels so we could hear without ear phones if we wanted to. I think we spent an hour or so running over songs before Van arrived. When he got there, he went to his microphone, pulled out some harps, and off we went. They were all performances, no overdubs, mostly first takes”.

Neil Drinkwater’s piano and Van’s sax along with Fiachra Trench’s string arrangements are the dominant elements of the instrumentals on Poetic Champions Compose , and provide a draped soundscape for the vocal cuts on the album too. The sound is mellow contemplation made musical – it facilitates the thing that it also embodies, and in this is remarkable in itself. The strings on these pieces both dress and release them from their moorings – listen to how the strings on ‘Spanish Steps’ (above) keep the weightlessness of the piece right up to the concluding instant 4.40-5.20, a superb example of how less can be more, the cinematic focus showing why Trench is in such demand for his film and TV scores.

The album’s supposed ‘ground-up’ improvised nature also attests to the special corner the composer found for his music here in his first trip to Wool Hall. The use of harmonica is illuminating too : ‘The Mystery’, the first vocal track of the album, opens with some short, trumpety, blasts of annunciation on the harmonica, all the more effective for its juxtaposed combination with the blue shades of the band’s sound and the pearl-drape sumptuousness of the strings. The album’s first vocal, opening ‘The Mystery’ some six minutes into its playing time, is like a landmark, a point of guidance from which to move forward – indeed it concerns itself with a movement into the mystic: “Let go into the mystery, let yourself go”. The strings which coil themselves around the melody are as smoke rings, highly visible but as insubstantial as air. It is didactic, “trust what I say and do what you’re told…there is no other place to be, baby this I know”, but Morrison seems to be cast as both master and pupil. The listener is drawn into a process and a state of mind but can be misled – as Morrison said during a lengthy meditation section of a performance of ‘In The Afternoon’ in Amsterdam in 1999 “we don’t want you falling asleep”, getting a laugh from the crowd – but this process of letting yourself go is preparing the listener: “I saw the light of Ancient Greece/Towards the one/ I saw us standing within reach/Of the sun” .

‘The Mystery’ is that of life and with a promised or at least posited alchemic consequence: ‘and surely all your dirt will turn into gold’: we see again how comfortably the idea of the Philosopher’s Stone fits as a motif for his work and the process upon which he himself is engaged. The idea of ‘letting go’ into the mystery finds a parallel in Morrison’s work not only in the theme of the mystic as a space into which one may come and go, but also in wider contexts: Alan Watts wrote that

“When you try to stay on the surface of the water, you sink; but when you try to sink you float. When you hold your breath you lose it –which immediately calls to mind an ancient and much neglected saying, ‘Whosoever would save his soul shall lose it”

and the idea of letting go into ‘the mystery’ is connected to this – it has to simply happen as opposed to being a concentrated physical effort – a letting go rather than a claiming of insight. The sound is typical of the album – spacious, each instrument heard in the round, matched with airiness, giving a dual sense of fullness and lightness. This matching of the heavy and the light matches the metaphysical mood of the material, grounded in material and earthly concerns (or should we say blues concerns) – love, loneliness, unhappiness – while having its gaze also turned upward to spiritual matters and sources. A song like ‘Did Ye Get Healed?’ is in all its simplicity directly metaphysical as it addresses the impact of the spiritual upon the physical. The sound of the track as laid down at the Wool Hall by this band is fully expressive of and in harmony with this kind of ambition for the music.

‘I Forgot That Love Existed’ is one of Morrison’s finest songs; a metaphysical tale of redemption through love which extends right back to the roots of Western civilisation to make the point that love is a universal presence and we need to tune into it and furthermore that it is a leveller as well as astep up from the ordinary life, with no-one particularly privileged or favoured– so that Socrates and Plato are brought to the table but directly on their heels comes “everyone who’s ever loved or ever tried” (67). It is almost a perfect late period 80’s Van Morrison song, especially in how the clean studio lines of the music illuminate the lyrical point; that is, it seems like a summation of what his thinking and writing had been aiming for over the preceding 5 years or so. Yet what stuns is its simplicity and directness – it is , like the rest of the record, a ‘small’ and compact sound, full yet full also of space. It flowers from a tight little knot of bass notes which are quickly joined by tentative shots of piano, their refusal of the major and the chord communicating a wise and cautious optimism. The beat is picked up by a light hi-hat at 20 seconds, and is awarded an affirmative ‘yeah’ by the singer at 23 and 29 seconds as he locks into the moment. It is not that love does not exist, but that he forgot that it did: we feel a parallel here with Hamm’s challenge to the sky in Beckett’s Endgame : “God, the bastard! He doesn’t exist!”. That memory is experienced emotionally – memory is such a theme in Morrison, particularly so in his work from the 80’s on, that it is worth noting that here he is working from a position of having forgotten (“I forgot that love existed”) and then the present being redeemed (“but now it’s alright”) by the act of remembering.

It is concise, spacious and presents a whole emotional landscape in which we are free to move. The switch to a stronger and more assertive beat, signalled by the entry of Neil Drinkwater’s synth at 0.52, beneath a far firmer repetition of the title phrase, makes the song step up a gear, and into the light – as the lyric says “…but then I saw the light”. This phrase is of course a commonplace, but one which Morrison would certainly know from the Hank Williams song of the same name ( if not the equally bounteous Todd Rundgren song), and it has connotations both religious and secular in its usages, a la ‘the writing on the wall’, which he used in ‘Full Force Gale’ a decade earlier. The lyric is unusual in that there is a flow to and from the singer and the world around him – often his meditative material is very intimate in its scope, involving the self and perhaps another (as in ‘Cyprus Avenue’ and ‘In The Garden’) but rarely far beyond these little cells of comfort. Here he makes a gesture which is almost Joycean ( ‘Here Comes Everybody’ , from Finnegan’s Wake) in its bold and extended inclusivity ‘everyone around me made everything alright’. Thus the intimate becomes the shared experience via the newly awakened perception of inter-connection : ‘everyone…everything…’.

He develops this theme in his references to the ideas and the thinkers that have endured down the ages “O, Socrates and Plato, they praised it to the skies/Everyone who’s ever loved, everyone who’s ever tried”. In this couplet he matches the enduring ideas of the immortals to the everyday experience of ordinary life, illustrating that there is no distinction between the experiences, only the perceptions of them: the first line picks out two ‘special’ points of view (Socrates and his pupil Plato) and connects them to the whole of humanity that preceded and also followed them ‘everyone who’s ever loved, everyone who’s ever tried’.

The song has at its centre a metaphysical conundrum worthy of John Donne himself “If my heart could do the thinking/And my heart begin to feel”. An inversion of traditional models of understanding human perception – head for ideas, heart for emotion – is posited (to use the philosophical term, as seems appropriate here somehow) and the song imagines what difference that would make “would I look upon the world anew and see what’s truly real? “ The element and admission of doubt is a properly philosophical mood, and the musical hue of robust caution matches this. It’s a wise song which is prepared to countenance the dissipation of that wisdom , if that proves necessary .

The sound of this album and its correspondence to its emotional and philosophical content takes another turn in ‘Alan Watts Blues’. Watts was a beat philosopher who ended up harmonising, without ever quite intending to, with the Hippie ethos of free love and alternative social programming. Dick Hebdige wrote about Watts in his essay ‘Even Unto Death: Improvisation, Edging and Enframement’(69), pointing out how Watts had understood the difference between the “genuine expansion of the frame of any art form and its conscious, stagey demolition in ‘experimental’ work”. Watts identified one incursion of Zen into creativity as the allowing of the accidental detail, in his essay ‘Zen and the art of the Controlled Accident’, a title which on its own clearly has some connection to Morrison’s own willingness to allow music to flow and develop according to its own energies and principles, rather than to force it here or there. Yet Watts also argues for the importance of what he calls ‘the frame’:

“A frame of some kind is precisely what distinguishes a painting, a poem, a musical composition, a play, a dance, or a piece of sculpture from the rest of the world. Some artists may argue that they do not want their works to be distinguishable from the total universe, but if this be so they should not frame them in galleries or concert halls. Above all they should not sign or sell them”.

Morrison’s whole career has been poised on this very fine line of division between the making of music and the framing of it – that is, the signing and the selling of it. Morrison has never been less than upfront about the nature of the music industry, in the aphorism that stands at the front of this book or in conversation (“Let’s not kid ourselves, the music industry is all about money” as he told Jeremy Marre in 2006) and his unflinching facing down of this fact has been his salvation as well the source of much trouble for him. Watts found fault with John Cage’s “silent piano recitals where the performer has a score consisting of nothing but rests…” (he is most likely referring to Cage’s infamous ‘4.33’) , which he considered “a group session in audiotherapy…not yet art”(71). The work of Morrison’s early favourite, Jack Kerouac, is indirectly critiqued here too , for its deliberate (as Watts saw it) placing of what Hebdige calls “his verbal clatter” against or outside the frame offered by verse or the novel. The puzzle is how to reconcile the organic internal logic of improvisation with the apparent paradox of deliberate spontaneity: ‘I am now going to make something happen without my stir’. Watts related this to what he called ‘the law of reversed effort’, as Hebdige points out, not unconnected to the saying ‘Whosoever would save his soul shall lose it’. In nature, according to Watts, the accidental is always recognised in relation to what is ordered and controlled. This serves as a decent annotation to Morrison’s working methodology, and as such draws together his techniques on the live stage and in the studio – the accidental moment is a function of arrangement and controlled structure. It is fitting then that one of his most ‘controlled’ and formally gorgeous albums has its roots in a moment where, as Martin Drover remembered, “we sat there and looked at each other..and said..What do you fancy, Van?”, and that this is the album which contains ‘Alan Watts Blues’, a song which doesn’t mention the man by name beyond its title, but whose influence is felt on almost everything else about it. Remarkably, it’s also the only Van Morrison original to include the word Blues in the title.

As a studio production it is a gorgeous sound, bright and crisp, and the zen-funk overdubs of Mick Cox add curlicues of lightness to its dizzy heels. It opens with thoughtful and tentative picking on a semi-acoustic guitar, before the beat ticks in at 0.19, beaten in by the vocal a second earlier. It clicks in on the space which opens between ‘I’m’ and’ taking’, anticipating the tap of the ‘ t’ in ‘taking’. The song draws in this busy but unobtrusive guitar, bright patches of piano and a determinedly metronomic rhythm into what, against the odds, is a very catchy pop song.

The chorus line is the title of one of Watts’ best known books, Cloud Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown, itself borrowed from an aphorism from the Chia Tao(73). In this the title flags up and acknowledges the influence of Watts; the song takes it from there, building upon that set of connections and inspirations. The melody is almost jaunty, the piano solo at the centre of the song sounding remarkably like Bob Andrews’ deliberately fragmented solo in Nick Lowe’s ‘I Love The Sound Of Breaking Glass’ reassembled and restored like a brightly hued stained glass window. There is a gorgeous and significant lift toward the song’s close at 3.59, when the chorus spills over into the verse and bridge structure in a manner which not only suggests an underlying unity of its constituent parts but actually delivers and reveals that unity, down to the eventual fade twenty seconds later. The mystery is retained and respected, but it also has a frame put around it, as Watts argued that it should. The ‘frame’ that the smooth, beautiful, studio-even surfaces of Poetic Champions Compose places around the complex music and lyrics within its eleven tracks illustrates how well Morrison can employ those textures when it serves his greater purposes. This is his smoothest album, while also being amongst his most experimental.

So at the Wool Hall on Poetic Champions Compose he achieved a kind of perfect fit between his ambition for the sound of a record and the lyrical, even philosophical ambition of the same songs; a delicate , responsive balance between smooth and rough textures, word and music, planning and improvisation, and between body and soul. Given his career-long habit of reaching a kind of perfected endpoint and then flying off in a wholly unpredictable direction, we should recall that his next record was not a further refinement of this sound, but a dive into the traditional songbook in his collaborations with the Chieftains. This tells us something of how he viewed the sonic fidelities of Poetic Champions Compose.

Oh, I Just Couldn’t Say… ‘Hard To Believe’

Having uploaded a piece on ‘Someday Man’ and ‘A Man Without A Dream’ to this blog recently, people were kind enough to say they liked it, and asked about other song analyses that were cut for reasons of space from my book The Monkees, Head and the 60s. There are lots, enough for another book almost. I’ve chosen one which shines a light on another Davy Jones tune, ‘Hard To Believe’, recorded for Pisces Aquarius Capricorn and Jones Ltd in late summer 1967 and which proved the opener for side two of the vinyl LP. It’s the least famous of the three ‘Believe’ songs of the original Monkees era (Peter said ‘I Believe You’ on Justus, of course) but it also seems unjustly obscure in their catalogue overall. So here are some thoughts on it. By my standards it’s a short piece (that may very well be a good thing) but I hope it is interesting and that it sends you back to the song.

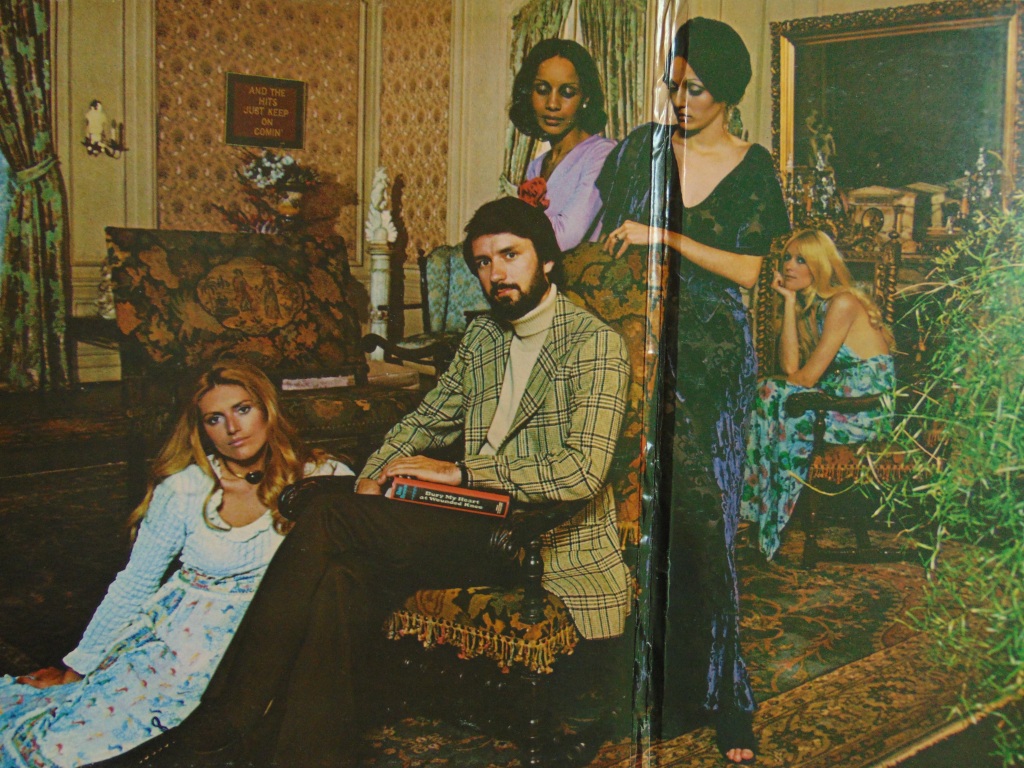

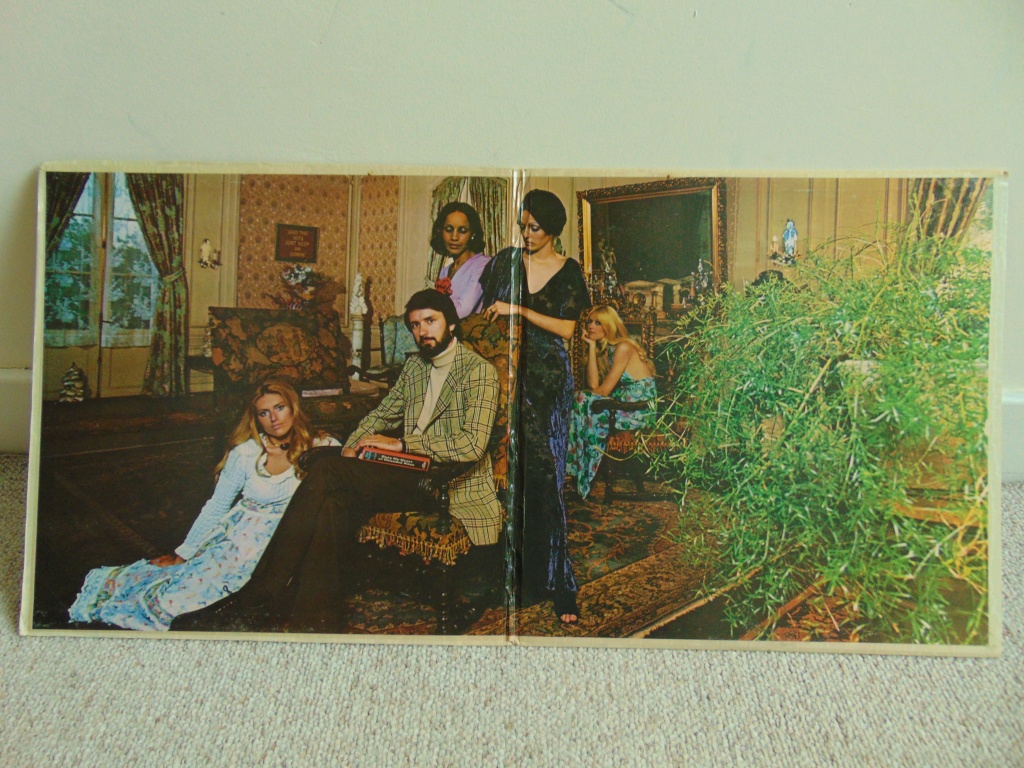

Who were the musicians in The Monkees again? Oh yes, that’s right, Michael and Peter. The curious fact is that Peter is seriously under-represented in numbers of tunes he had on their albums; Micky and Davy equal him in the number of credits for ‘real’ songs. ‘Hard To Believe’ was a co-write between Jones, Eddie Brick and Kim Capli, vocalist and drummer respectively of The Sundowners, who had provided back-up for The Monkees on the summer ’67 US tour. Capli certainly took charge of the process, effectively recording and performing the entire track himself, a la primetime Prince or Stevie Wonder, being credited with bass, claves, cowbell, drums, guitar, percussion, piano, and shaker. In fact everything but the lead vocal, strings and the sublime, summertime brass. In this it was the first Monkees track to be built up in this modern-feeling way – part by part, slowly assembled instead of striving for take after take as an ensemble. In this it signalled that once again the methodology was changing, this time aided and abetted by the new 8 Track recording technology at RCA that Capli was clearly delighted to get his hands on. Chip Douglas told me that he had mixed feelings about this but, as effectively an employee of the Monkee project he was not really in a position to object – ‘I really wanted them to build on the way we had done Headquarters and consolidate the group identity, not relying on outside input, so everything you heard was Davy, Mike, Micky and Peter. And me sometimes of course! But they seemed to lose interest in that idea, and wanted to reach out, which I also understood. But I felt they missed a chance there, and I wished they’d gone that way a bit more.’ (Chip Douglas to Peter Mills, July 2015)

The album is certainly different from the garage band sound of Headquarters, but is still in my view a real highlight, it has a flow and sophistication which speaks of the collaborations as well as their own fluent, buoyant confidence as world best sellers. Capli and Brick didn’t splash too much on their Monkee connection though, that was left to bass player and notional head Sundowner Bobby Dick who contributed a number of articles to teen magazines in the aftermath of the tour – instead Capli in particular enjoyed the access to top of the line studio time it gave him, and with this song crafted a superior slice of lounge lizard soul. Chip Douglas has a point though – it was this kind of connection with other musicians who may actually have been closer musically to the individual members than they were to each other, therein being the difficulty. It was the first song Davy had written that did not involve the other four and was not a one-off- in the period following Pisces, up to The Birds The Bees and The Monkees he wrote a bundle of tunes, some good, some shaky, but all the products of verve and hard work – ‘Dream World’, ‘The Poster’, ‘I’m Gonna Try’ and notably ‘Changes’ (a possible try-out to pen the theme song for their movie under its working title) and – look – a protest song of sorts, ‘War Games’. This represents quite a run of work, and indicative of the ‘Broadway Rock’ that he wanted to pursue under the auspices of the Monkee brand, that he detailed on the Hy Lyt interview in support of Head. Indeed perhaps the best ‘Broadway Rock’ number he sang as a Monkee was Harry Nilsson’s ‘Daddy’s Song’ for that movie. Anyway let’s hear ‘Hard To Believe’ and its smooth Latin-Soul shuffle.

Back in the summer of ’67, where all things must have seemed possible, this neat and precisely constructed little musical parfait was smooth and shimmery, concealing a nutty kernel in the form of the lyric, telling a story of possible betrayal – ‘I try not to hear the things you say about me’ – in balance with the chance of redemption for a love – ‘And if you feel what I feel, you won’t go away’. It’s a perfectly executed little match of melody and lyric, and benefits from a tidy brass and string part dubbed on at a session on September 15th – the lounge quality connects the song to the atmospheres that the mock -intro/outro of ‘Don’t Call On Me’ tries to create. In the wheels within wheels that often surround the many people associated with The Monkees, the arranger for the strings and brass was George Tipton, later celebrated for his work with Monkee songwriter and buddy Harry Nilsson.

Starting out with a neat little rhythm – a kind of near-Latin swing, mainly rimshots on the snare – a couple of strokes of guitar, some feathery touches of Bacharachian brass and we’re in. Davy’s vocal finds a perfect slot in this mix, steering clear of the harsh edges the power of his delivery could sometimes bring – the echoes of the Northern English music hall – and instead moving from gentle to pleading to philosophical to soulful across the verses. The mood of the song itself is his; and as such represents the first stages of the third phase of Monkee music, that is, effectively four different inputs onto one album. Remember this tune is followed by the band’s first ‘full-on’ country-rock track ‘What Am I Doin’ Hangin’ Round’ and shares a side with the pop perfection of ‘Pleasant Valley Sunday’ and the moogy-future overload of ‘Star Collector’ and the sound action painting effects on ‘Daily Nightly’. To drop the needle at the start of side two and catch the nifty little rimshots which lead into this track and follow it through to Micky’s fading ‘bye bye, bye bye, bye bye’ at the side’s end is quite the trip, musically speaking. So a nice stretch in the sun, which this tune feels like to me, is a good way to begin.

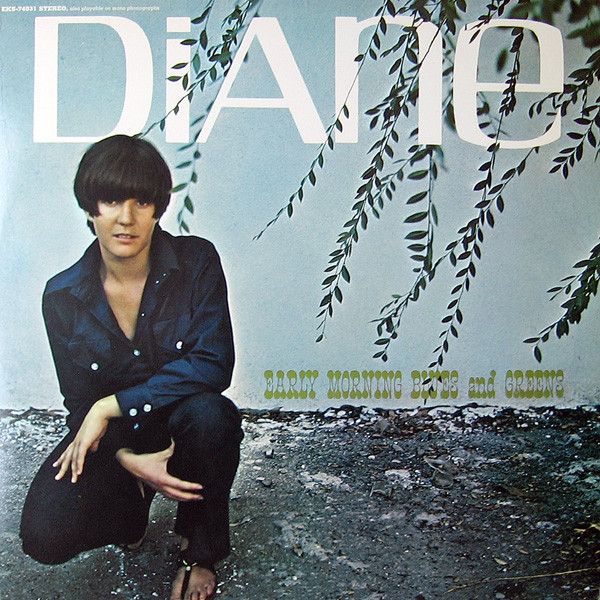

It’s the story of a love affair gone wrong – so far, so teenage’d – but it also has some darker more adult shadows flitting across it and as such the breeziness of the music and the ambiguities of the lyric are an intriguing match. They move from hurtful gossip – ‘I try not to hear the things you say about me’ – to a final declaration, ‘I love you, I need you, I do love…you…’. Jones’ voice traverses the melody very pleasingly – listen to how he sings the opening lines of the third verse ‘Now you must believe that when I saw you today, Oh, I just couldn’t say…you held his hand the same way’ (1.36-1.50). There’s some of the teen idol business in the first part but this has grown into something truer on the pivotal point of that ‘Oh’ and the expressive tenderness implicit in ‘I just couldn’t say’ and the emotional realisation of ‘you held his hand the same way’ – she’s gone. So – the loss is acknowledged in the tone and intensity of the voice here, even as the lyric provides the possibility, at least, of a happy ending ‘ But as I turn my heart still wants to say…’ and the final lines add a heartfelt quality to what could have sounded stagey but escapes that by virtue of the sophistication of the arrangement matched with the emotional range of the vocal. Jones is sometimes thought of as what my Father used to call a ‘belter’, that brassy overdriven showbiz delivery – and indeed sometimes he strayed into this territory feeling quite at home with its theatricality – but he was also an highly adept singer, sensitive to the meanings as well as the shapes of words and melodies. ‘Hard To Believe’ gives us one of his best vocal performances, in my view, to be placed alongside ‘Early Morning Blues and Green’s and the first ‘You and I’ as examples of where his voice could explore when the song suited him. And I haven’t forgotten the thrill when I heard its little Latin tempo kick in at the 2011 show in Sheffield, England. Here’s a clip from the US leg of that tour, with Micky very capably supplying those all important Latin touches. What a team they were.

The last lines on the studio original are doubled by a second vocal, and the final ‘You’ is rewarded with a high harmony of the sort favoured by Chip Douglas, and the track drops away slowly and deliberately thereafter, leaving the bass and drums to the fade and a little vocal lick ‘shoop-shoop-ahh!’ I’d always heard this voice as being Nesmith’s for some reason but Sandoval does not list him as being involved in this track in any way so perhaps not. Indeed the track did not feature any Monkee other than Davy and as such is indicative of the way things were panning out for the group. Chip Douglas told me that the circumstances under which Headquarters had been recorded six months earlier were the exception, where they were able to devote all their time to the studio, to the music, and they were between the making of the two TV series. By the summer of ’67 they were busy again, gigging, filming, planning a movie…so it was even harder to get all four of them together and work in the manner they had employed on Headquarters, even if they had wanted to. They may have felt a bit of ‘been there done that’ with the ‘four of us’ mode of working and, as anyone who has made an album will tell you, it’s hard work and there are often long periods where little seems to be happening – it can be boring.

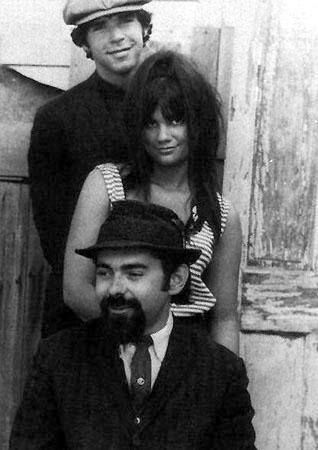

So they didn’t have the time, nor the collective will to make another album like that, although Pisces does have all four of them on plenty of the tracks. This was something Chip Douglas wanted to ensure happened, to guard against what eventually came to pass, that they would just work separately and then pitch their tunes for inclusion on a Monkee album. So the centre, eventually, could not hold – but while it did, the albums yielded a rich mix of musical styles and forceful , familiar personalities. The sleeve of Pisces showed it best – a front image by Bernard Yezsin of the four Monkees, their facial features blank, standing in a field of flowers with the group’s guitar logo half-buried. The drawing was based on a photo of the group Yezsin had taken. The back cover shots were by Henry Diltz, friend and musical collaborator of Chip Douglas; Diltz became the default chronicler of the Californian rock scene of the late 60’s and early 70’s. His black and white shots for Pisces show the Monkees together, but separate.

And who is playing guitar? Peter, of course, but look – Davy. Hard to believe? Maybe. But true.

Tomorrow’s a new day, baby: The Monkees and ‘Someday Man’

Another in the occasional series of pieces which didn’t make it to my book The Monkees, ‘Head’ and the 60s, a volume which Michael Nesmith, Bob Rafelson and Jack Nicholson all praised to my face. Did I mention that before, somewhere? Might have done. This close look at ‘Someday Man’ and its unjust obscurity was originally part of the chapter ‘Listen To The Band: the Music of The Monkees’, in the section focussing on Davy Jones’ contributions to the songbook.

I’ve also included a bonus doodle, on ‘Someday Man”s session-mate, Goffin and King’s ‘A Man Without A Dream’. The other absentee from the Davy section is ‘Hard To Believe’, which I might post if folk are interested. Anyway, I hope there is something of interest in here for you.

By the time ‘Someday Man’ was issued as a stand-alone single in 1969 – April for the US, June for the UK – the vertiginous drop in the band’s popularity was there for all to see. Peter Tork had quit after the dismal TV special and the commercial belly flop of Head – not because of these failures, but just because it was time. Unlike similar walk-outs on comparable successes, where the bands were still maintaining sales and popularity – Brian Jones, Paul McCartney – Tork’s departure coincided with decline, but was coincidental with rather than a response to the band’s falling stock. The remaining three, bound together by both a loyalty forged in their unprecedented shared experience and contractual obligation, ploughed on. Looking at it from here we see the writing scrawled unmistakably on all four walls but back then a positive spin was put on the situation, especially by Nesmith. In some ways Tork’s departure tipped the balance of power within the group, and Nesmith was now the undisputed musical ‘boss’; determinedly viewing the role of a Monkee as what it was – something he’d signed up for, rather than something with deep roots of the sort engendered when a band starts from nothing and achieves success – he saw the chance to develop his own musical interests and span it as the three of them following their own musical paths under the ‘umbrella’ of The Monkees, with all the access to resources and promotion that the brand name brought. In fairness, this would probably have happened anyway as the quartet grew into themselves and the project that became The Monkees Present had originally been mooted as a double album, with each Monkee having a side to themselves. Four aspects of the same thing, or a recipe for a break-up? It depends. Pink Floyd did something similar with Ummagumma which emerged in the same month as The Monkees Present (October 1969) so clearly the idea of the many-in-one was in harmony with the zeitgeist, even if it spoke of some internal disharmony.

In 1968, while still a quartet, Nesmith had told the venerable English music weekly the Melody Maker that

“We are going to try and abandon our collective identity. We are not represented by one idea. By a pattern of record releases and exposure, we will be able to make the transition from the collective identity. Each of us will be able to spring out to do what we want within the context of the group” (‘The New Monkees’ Alan Walsh, Melody Maker, 1 June 1968)

In this we see a grand design, an order of planning that is not untypical of him – sometimes he has been able to make the plan come to fruition, sometimes not, but the ideas are always there, expressed in this free-flowing, professorial manner and they are usually Big.

Around the same time, Micky had also spoken to the same paper, telling Alan Walsh that:

“The Monkees are four individuals. We’ve never socialised too much together, and in the future we’ll be going in our different directions — but still as the Monkees.

We’ve always been individuals and the best example of this will be seen in our next album. Each track is produced separately by one of us and, naturally, our particular musical preferences and scenes emerge strongly.”

But where are the Monkees at, musically?

Micky explained: “Well, Mike is into orchestras, big bands and things. Peter is involved in hard rock and psychedelic music. Davy is back with the Broadway show things that I like, too. Myself? I’m very interested in electronic music and electronics generally.” (MM 1/6/68)

The album he refers to may well be the projected project which became Present over a year later, with the symmetry of the quartet reduced to a EP-sized four tracks, being a third of an album each. We never got to hear a full exposition of Peter’s ‘hard rock and psychedelic music’, the only examples we have are his two scorching tracks on the soundtrack for Head . Of the remaining trio, only Davy’s nominated style could be said to have made it onto Present or Instant Replay; Nesmith’s contributions are effectively blueprints for his country-rock direction post-Monkees and Micky’s are series of one-offs all of which showcase the skill, depth and range of his voice but do not conform to a recognisable style of genre. That’s good, but doesn’t allow for a stylistic musical focus to develop in the way it did with Nesmith, although it is equally faithful to the notion of Micky doing what he wanted ‘within the context of the group’.

Scrolling forward to February of 1969 the quick release of Instant Replay saw the Monkee project trying to recover from the multiple blows landed in the last three months of 1968- the cancellation of the TV show, the failure of movie and the TV special, the decline in record sales, Peter’s exit. Part of this was addressed b y the fabulously rich-colours of the LasVegas photo shoot by Henry Diltz in which the trio look tremendously at ease with the new situation, and also shots where they pose with the evidence of their success, gold discs and all, just to remind everyone who they still were. This found a musical correspondence with an ill-advised choice of single. In a piece of pre-Rhino archival work, a foundling from 1966 called ‘Tear Drop City’ was resurrected and issued in February 1969- it is in Monkee terms a pre-revolutionary artefact, an early track recorded across sessions in October and November 1966 featuring the Candy Store Prophets, written and produced by Boyce and Hart.

One can see the business logic ; backpedalling furiously from the untenable commercial cul-de-sac they found themselves in, Columbia and Screen Gems will have encouraged an upfront return to the sound and style that first made them such a hit. Explicitly so in this case as ‘Tear Drop City’ is less of a kissing cousin and more of a Siamese twin of ‘Last Train To Clarksville’, right down to the Louie Shelton riff and chugging rhythm. It is certainly a good if workmanlike example of the early style and one which no amount of studio time in early ’69 could have replicated, six months on from the elegiac chorale of ‘Porpoise Song’. When I first picked up a copy of Instant Replay in around 1977 (thank you Gerol’s Records, Merrion Centre, Leeds once more) I was amazed to hear this track and how faithfully it recreated (as I then thought) the original sound of the band – the album sleeve gave none of the historical recording information we find on the reissues so I just took it to be an effort to recapture that early style. Likewise I had no notion of where the album stood in their career, how well or not it had sold or of anything at all. I just had the music. If the exhumation of a rejected tune or two from the golden era showed a little twinge of boat-steadying panic, the rest of the album did indeed speak more truthfully about the state of play at the time, with a mixture of Broadway Rock, Country Rock and Dolenz One-Offs.

In amongst this ball of confusion Davy Jones finally managed to persuade Screen Gems to allow him to record a song they did not own. This in itself can be read as evidence of a loosening grip on the project by the studios driven by the realisation that the heat was going out of the project, a long-ish goodbye which let ultimately to the almost unnoticed sputtering out of the early 70’s. That’s as may be but it allowed Jones to bring in a song by a young singer-songwriter Paul Williams. He already had a track record, having auditioned for The Monkees back in ’65 and been writing songs on the scene alongside writing music for TV and advertising campaigns. He wrote with Biff Rose and they came up with ‘Fill Your Heart’ which you will find at track one, side two of your copies of David Bowie’s Hunky Dory and later had huge success with Roger Nichols on hits for The Carpenters (‘Rainy Days and Mondays’, ‘We’ve Only Just Begun’ which started life as a song in a banking commercial) and Three Dog Night (‘Out In The Country’, ‘An Old Fashioned Love Song’). Three Dog Night are another group with a Monkee connection having been given their name in 1968 by June Fairchild, the transcendental beauty from Head who was dating the band’s Danny Hutton at the time. In some ways Williams’ songs were the soundtrack of early 70’s America, taking up the mantle of Jim Webb and occupying the space between the death of the 60’s dream and the arrival of the Californian Cowboys.

He started out, however, as do we all, with hopes and energy which he put into circulating demos of his material, including the then unusual step of privately pressing up two albums of songs he had written with his friend Roger Nichols and distributing them as he could. The second of these contained a song called ‘Someday Man’. Davy Jones said that he loved Williams’ work from the first hearing and we can believe it – well structured songs, strong lyrics, ready-mades in effect – but it was not until he proposed ‘Someday Man’ as a Monkee track that the connection became live. Here was a song which fitted well with Jones’ own interests and strengths, had all the components of a hit in the pop scene of 1969 – a real find. The first hurdle to clamber over was that, as Bill Martin discovered in the case of his ‘All Of Your Toys’ back in early 1967, the watertight contracts which locked in outright ownership of everything Monkee to Coilumbia and Screen Gems meant that only songs published (that is owned) by Screen Gems would be issued under the band’s name, ensuring all possible monetisation from a song or anything associated with the group would stay in-house.

As noted, perhaps the unmissable decline in the group’s commercial fortunes forced something of a rethink and permission was granted to Jones to go ahead and record the song which was published by Irving Music, associated with A&M, the hip easy listening label of the period owned by Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss, where Williams’ sound found its natural home. In 1970 however his debut ‘legit’ album Someday Man was released on the Reprise label which, despite being Frank Sinatra’s own imprint, was and remains synonymous with a tougher brand of singer-songwriter than Williams is perceived to be.

Regardless it is arguable that Jones recording Williams’ tune did him a great favour and him titling his album after the song shows it was to some extent his calling card at this time. It did The Monkees and their fans a favour too, giving us a late career highlight albeit one which drifted by almost unnoticed at the time, reaching only the lower reaches of the pop charts in the US and UK. My battered UK RCA copy of it – 15 pence, Project Records, 1977 – had clearly been well-loved though, as had its b-side, Nesmith’s ‘Listen To The Band’. From the perspective of 2016 that is a heck of a double-header; the day I bought the single they were two tracks I’d never even heard of, let alone gone looking for.

Let’s listen to Paul Williams’ recording of the song on the above album.

Davy reminisced about how he came to record ‘Someday Man’:

“I went to Screen Gems many,many times with Paul Williams tunes…but they felt they were too sophisticated. This one was all right. They accepted that. It was a bit complicated for the Monkees at the time. Unfortunately it never even got a showing. I thought Bones Howe was a bit busy. I felt they were all a bit busy. Carole King telling us how to sing it. Bones busy throwing too much in there. ‘My budgets are usually this much, so I must keep them up there.’ The Monkees were a garage band and we needed the basic instruments – the rest was personality’.

Whether you could actually ‘do’ Paul Williams without the faintly smothering squabs of arrangement cuddling up to the tune is debatable – like Jimmy Webb the arrangement can sometimes seem the key component – but Jones makes a good point about everyone being ‘busy’ around the band’s music, sometimes over-arranging, over-egging the pudding. Yet this is part of the price they had to pay for drifting away from the ‘garage band’ they became on Headquarters – outside of that guitar bass and drum lie the territories of the ‘busy’ arranger. Dayton Burr “Bones” Howe, mentioned here by Jones, had come to the band off the back of great success with The Fifth Dimension where he had balanced their richly stacked vocals with a keenly soulful edge, just avoiding over-production with flat-out groovy takes on Laura Nyro’s ‘Stoned Soul Picnic’ and ‘Wedding Bell Blues’ and Ashford and Simpson’s ‘California Soul’ which, in a version by Marlena Shaw, became a huge tune in the UK Northern Soul scene. Promising much, he could have proved as influential on a new Monkees sound as did Boyce and Hart and Chip Douglas before him. As it turned out he only produced two studio cuts for the group, both featuring Jones as the only Monkee to make a contribution; one was ‘Someday Man’ and the other Goffin and King’s ‘A Man Without A Dream’. These tracks were originally recorded in an afternoon on November the 7th 1968, the day after the New York premiere of Head and is a full-on return of the Wrecking Crew to Monkee duties, featuring Tedesco, Blaine and Knechtel to name but three. No Monkees in the house as they were all in Manhattan, starting to absorb the hail of indifference and scorn which greeted Head.

Bones Howe recalled how he and the song arrived at the session:

All the Monkees were making records on their own and Screen Gems were looking fro somebody to produce Davy. So I did those two tracks with him, ‘Man Without A Dream’ and ‘Someday Man’…Paul Williams and I were friends going back for a long time…I played it for Davy and he liked it. We were able to convince Colgems that we could do an outside song…I kept saying to them ‘Find me another song that’ll knock this one out of the box’. And no-one could find a song that everybody liked better’. (Sandoval p.212)

Using the indisputable logic that a good song is a good song, and willing to allow some rule-bending in the hope of revitalising a sagging franchise, the suits at Colgems acquiesced and the session went ahead. Nearly forty takes of ‘Someday Man’ squeezed into an afternoon session resulted in a composite version, matching best take to best take via some judicious editing and dropping-in. We’ve come full circle from the debut album, but the resulting track has a warmth and brightness which adds to its inherent appeal. As Jones inferred, it is a little overdone but I’d argue that Williams is a writer whose work lends itself to this curious of mixture of directness and complexity – one only reflect upon the towering confections created by Richard Carpenter around Williams’ songs to see that – and ‘Someday Man’ is a good example of this. It is smooth, slipping down like a Brandy Alexander, but is also indeed verging on what Jones called ‘busy’.

The track is like a compact composite in itself – how do these parts fit together? When I first heard it I wondered how all these parts could be part of the same song. I like this in a songwriter’s craft and it is often the sign of a cup overflowing with ideas and is exciting to listen to – keep up or you’ll miss it! – the most obvious example being Brian Wilson and his pocket symphonies like ‘Good Vibrations’ and ‘Heroes and Villains’, or Paul McCartney’s fabulous ‘Back Seat Of My Car’ or the better known ‘Band On The Run’, all of which assume several different shapes within their overall structure. Jimmy Webb did it too – think only of ‘Macarthur Park’. Pop is generally modal and structured fairly straightforwardly so songs which undertake a winding and surprising path, and do it well and with good reason are to be cherished.

Opening on a rising bassline – among the busier participants in the track overall –and a brisk proto-disco hi-hat, the song is joined by a rather airy and gorgeous brass arrangement courtesy of Bill Holman calling down French Horn, trumpet and trombone. Davy’s vocal is a little muffled, probably due to the saturation of sound on the tape and the multiple bounce-downs required to accommodate everything, but is plenty clear enough to hear that he likes the song and is responsive to its internal dynamics, from the skipping , almost staccato topline of the verse and then into the tempo-shifted, razzamatazz’ing chorus, highkicking its way into view. Davy’s vocal takes its cue from the Williams demo, pitched and delivered with the same speed and space – the demo was undoubtedly constructed and performed to appeal to him or someone like him. Williams’ own version , which provided the title of his major label debut in 1970, is pitched lower and produced with an emphasis on a steadier backbeat and carefully stacked background vocals – again in this we can see why his songs appealed so much to Richard Carpenter.

The early backing track take included on the Instant Replay box set uncovers the rather gorgeous piano part buried on the final single; it installs the ‘one-two- threefourfive’ rhythm which is the secret centre of the song. This is clear on the Williams demo, leading off with the piano part but lost in the detail of Howes’ production – on the box set we hear it anew like the details suddenly visible on a restored painting.

The song has three main sections – so far, so verse, chorus, bridge – but it feels more intricate than that conventional pop structure suggests because the changes involve shifts in tempo and musical texture as well as chordal or harmonic switches. We can say the first section runs from the opening to around 0.28, where the little step up to the chorus is cued but, very cleverly, not delivered – the vocal changes and prepares the song (and the listener) for a change before it comes. It’s like a little airlock in the song’s structure, facilitating passage from one section of the piece to another. A mounting pulse on the snare allows the chorus in , beginning with the line ‘I was born a someday man’. In this chorus we have a new beat, a whole other rhythm, stepping into the ease of that high-kicking swing as opposed to the busy-bee energy of the verse and its rhythmic patterns. Just when we think that’s it, yet another section hoves into view; the ‘Tomorrow’s a new day’ baby’ functions as a kind of bridge back to the intro and verse part but is so much more than that – the piano steps forward giving the rhythm yet another shape, echoing and illustrating the optimistic urgency of the lyric.

A key element of Howes’ arrangement is the fuzztone guitar stroke which keeps the beat throughout which is best heard early, first every four beats and then when it breaks into double-time at 0.12 and thereafter repeating under Jones’s vocal every two seconds, marking the time musically and figuratively, for at the verse’s end the lyric asserts it ‘has all the time in the world’. A nice touch, particularly because the song’s overarching subject is time, and how much we have of it at our disposal – it is waiting for the future, waiting for tomorrow, for the ‘Someday’ on which things begin. Occupying a kind of benign purgatorio, the song is about coming into being but not quite, for when you are waiting to begin, all is possible – ‘tomorrow’s a new day baby, anything can happen, anything can happen at all’ The on-beat handclaps in the bridge add to that urgency and forward momentum. Appropriately for a song written by a man who would deliver great success to A & M, the horn arrangement speaks of Herb Alpert, bright and sure but also sensuously muted and smooth. It also strikes me as the kind of song Jones could have built a solo career on had The Monkees got out earlier and not allowed their reputation to sink to the level it did by the time of Changes and ‘Do It In the Name Of Love’, the Monkee single that dare not speak its name. As Jones often lamented , being an ex-Monkee was more of an impediment than an advantage in the early 1970’s, when precisely this kind of music was dominating the hit parade. In connection with this, ‘Jesamine’ hitmakers The Casuals had the nerve to compete with the previously invulnerable Monkees by recording and releasing their own (and not too soundalikey) version in 1969.

Lest we forget, ‘Someday Man’ was never included on a contemporary Monkees album so unlike its b-side ‘Listen To The Band’ was never caught on the (apparently) more secure format of the long-playing record, as opposed to those flashy, mercurial 45s. This is partly due to Williams’ success in the ‘hip easy listening’ era of the early 70s and also to the way the reputation of The Monkees’ music has grown in the decades since the song was recorded. The reissues programme via Rhino and the multiple box sets have appended the song to Instant Replay for the most part, or it has stood alone on the more ambitious Best Of sets. It was also included in what still seems to me the ultimate fan-pleasing setlist for the 2011 reunion tour. Davy introduces it here with a bit of classic self-deprecation, calling the diminutive Williams ‘the only guy I could look straight in the eye’. I saw this show in dear old Sheffield (the city which hosted First National Band gigs in 1970) and was ecstatic to see and hear Davy Micky and Peter doing the right thing by their back catalogue; this was one of many Songs I Never Thought I’d Hear Sung Live By The Monkees in that set. A few years ahead of Dua Lipa, I was levitating.

Speaking of musical as well as calendar time, the sheet music of this song, seen at the head of this piece, suggests ‘Moderately’ as its tempo and so it is, but it is a restless moderation. A shot from the Henry Diltz Vegas portfolio was used as the front cover image of this song’s sheet music and the song has something of that new beginning optimism about it; it feels eager to get started and the quick shifts in tempo only add to that sense of possibility – tomorrow’s a new day baby, anything can happen, anything can happen at all.

Bonus

The hidden twin planet to ‘Someday Man’ is ‘A Man Without A Dream’, the Goffin and King composition which made it, unlike the Paul Williams song , onto Instant Replay. It follows another mid-paced Brill tune, Neil Sedaka and Carol Bayer’s ‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’. Unlike Goffin and King, Bayer and Sedaka had not had songs of the quartet of albums intervening between More Of The Monkees and Instant Replay and, well-made as it is, the presence of their tune here is further proof that the experiment was over. ‘A Man Without A Dream’ precedes Micky Dolenz’s own mini-opera ‘Shorty Blackwell’, about which he has seemed somewhat embarrassed when asked for his views , calling it ‘incredibly self-indulgent’. Maybe, but it is evidence of freedom, which is what they fought for and gained, it is not untypical of its time and is also actually quite good, in my view. So the Goffin and King song sits symbolically between the well-crafted if unexciting Brill Building tune and the singular audacity of a home-grown freak-suite. It manages to link the two tolerably well in the running order, being a piece of elevated MOR, nowhere as charming as ‘Someday Man’ but using the same basic ingredients. Here is a quite different and rather soulful early take, showing a classic pop root, before the arrangement got busy.

Davy’s remark about ‘Carole King telling us how to sing it’ no doubt refers to her attempted input into the recording . Goffin and King had songs on five of the nine original Monkee albums and as such will have felt proprietorial toward them and how the songs were handled – recall Chip Douglas’s tale of King being annoyed by some perceived slight via rearrangement or lyric change on ‘Pleasant Valley Sunday’ – and this song is much more in the vein of the first two albums than those which followed it. Jones liked the song and the singing of it, commenting that Howe’s chief virtue in his eyes was that ‘The producers normally had me singing high up all the time. Finally I’m in the range I should be singing in. I’m a baritone’. (IR booklet) . Here’s a gorgeous early vocal take that suggest a different kind of song.

The low number of takes needed to get a satisfactory vocal (four) would seem to suggest Jones did indeed take naturally to this tune. I’m not sure I agree that it shows his voice at its best though, preferring as I do his pop-soul voice to his musical theatre voice, but one can feel the ease with which he sinks into the song., and Howe’s arrangement owes something to that superior brand of MOR soul that carried much weight in the late 60’s, not least through his own work with the 5th Dimension. The lyric is a well-articulated explanation of emotional ruin, specifically detailing the unhappy state; in this it is the reverse of the as yet unclarified optimism which courses through ‘Someday Man’, with its eye on tomorrow rather than the bad breaks of yesterday. So here is the finished article, all tux’d up.

So the two tunes we have looked at here make quite a logical pair. Bones Howe’s arrangement of Goffin and King’s tune is stately, allowing more space for the voice to explore the tonal moments, and the brass is once again very well charted by Bill Holman doing no more and no less than the song needs from them. It’s clear why ‘Someday Man’ was preferred as a single but even in its ornamental state, ‘A Man Without A Dream’ is the former song’s reality check, the comedown after the fizzing brightness.

Sock It To Me: The Monkees and ‘Goin’ Down’

This is one of my occasional posts of material left on the cutting room floor of my 2016 book The Monkees, Head and the 60’s. If you like it, check out my book here http://jawbonepress.com/the-monkees-head-and-the-60s/

What’s the connection between Mose Allison, Breaking Bad and The Monkees? We’ll get to the TV show but Allison was (and remains) like The Monkees in being an exception as well as an example in his particular field. He was a white man playing jazz piano, effectively inventing a way of singing which has proved hugely influential in jazz, a kind of adaptation of the sound of a horn put through the human voice. Georgie Fame is the UK’s most famous Allison acolyte, and demonstrates the technique as he takes half the leads on the 1995 album he made with Van Morrison of Allison’s songs, Tell Me Something. A song which isn’t on that album but which is one of his most famous is – in the jazz tradition – an adaptation of someone else’s tune.

‘Parchman Farm’ began life as a blues written and sung by Booker T. Washington (aka Bukka White) as an autobiographical sketch – from 1937 Washington had served time in a state penitentiary in Sunflower County, Mississippi called Parchman Farm for shooting a man in the leg in 1937. His crimes were lesser than those of Huddie Ledbetter but like Leadbelly he was recorded by John Lomax for the Library of Congress in 1939 and he was released the following year. Lomax’s magic touch when it came to securing the early release of his favoured blues singers from jail seems also to have worked in Washington’s favour and he was freed in early 1940. A session in Chicago directly after his emancipation modernised his Delta Blues sound, and caught ths version of the song.